New Release This Month

M/M historical romance

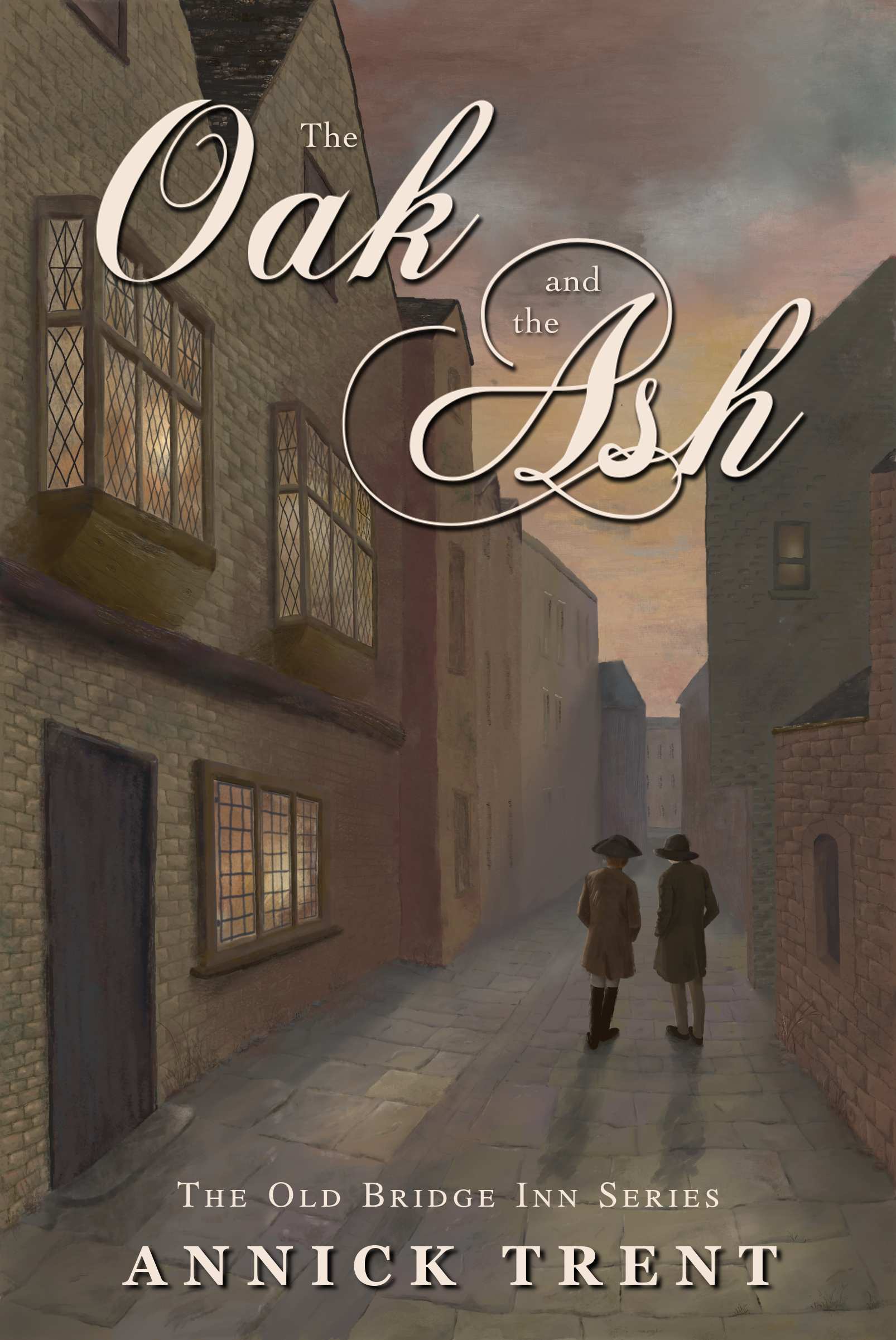

Back again with a new release! The Oak and the Ash is a historical M/M romance about a surgeon and a valet whose tentative relationship is cut short when they find themselves testifying on opposite sides in a murder inquiry...

Radical surgeon George Evans is called to the scene of a midnight duel between an earl and his cousin. Despite the strained atmosphere in the house, George finds he must stay and tend to the injured duellists. Fortunately, his sojourn is made more than bearable by the earl's quietly competent and oddly attractive valet, Noah Moorecott.

Under his reserved exterior, Noah turns out to have a wry sense of humour and a passion for reading to match George's own. The more time the two men spend together—whether enthusing over natural philosophy or arguing over politics—the closer they grow, quickly becoming friends, then lovers.

They live in two different worlds, but it seems nothing can keep them apart—until they find themselves on opposite sides in a murder inquiry.

The Oak and the Ash is set in the same fictional universe as Beck and Call and Sixpenny Octavo. Some familiar faces reappear, but each novel is a standalone romance.

Like the other books in the series, this is set in 1790s London, during Pitt's "Reign of Terror". It contains a little politics, plenty of romance, and lots of geeking out over the history of meteorology.

The Oak and the Ash

Chapter One

The inn lay several miles off the main Dorchester to Salisbury road, and George Evans was the only traveller in the taproom that evening. The other drinkers were all local men. Over his late supper of bread and onion soup, George fell into conversation with two men from the village, but they left when the clock on the mantel struck eight, bestowing a few final pieces of contradictory advice on him.

“Do ‘ee take the path beyond the millpond tomorrow morning, that’ll set you on the right track,” one of the men said.

“He’ll never walk to Salisbury in time for the stagecoach if he gets lost on the downs. Stick to the road, young man, that’s my advice,” the other man said.

“Are you addled in the head? It’ll take him an extra half an hour to walk around by the road.”

“Aye, but if the carter passes him on the way, he’ll get a lift as far as East Martin, won’t he?”

Still arguing amiably, they pushed open the door and disappeared out into the night. The taproom was almost empty now. The innkeeper came to take away George’s bowl and offer him another pint of ale. George shook his head.

He carried a candle to his room and sat down to read the book he had brought with him: a short pamphlet on the principles of natural philosophy behind Kinnersley’s touring displays of electrical phenomena. The pamphlet was only six pages long, but he could not seem to get much further than the first line.

Tomorrow evening he would be in London. He could not help feeling that he was returning with his tail between his legs, his trip a failure. He had left London with such high hopes, and now he felt a fool.

The candle had almost burned down. George set aside his pamphlet. He slumped back in the chair, rubbing his eyes. He should really lie down and go to sleep.

A sharp rap sounded at the door.

“There’s someone here as would like to see you, sir,” the innkeeper’s voice called from the other side.

George rose to open the door. In the corridor outside stood the innkeeper, accompanied by a dark-haired man, slightly built and smartly dressed. This latter fellow ran his gaze over George with a measuring eye.

“Good evening, sir. Are you a surgeon, by any chance?” he enquired. “The innkeeper believes he heard you say you were.”

“Aye, I am.”

“Excellent. My name is Moorecott. I work for the Earl of Warbury. You’re needed at Dunstan Lodge, if you would be so kind as to accompany me there, Mr… Evans, is it? There’s been an accident.”

George suppressed a groan. He had come twelve miles on foot today, and tomorrow morning he planned to rise early to be in Salisbury in time to catch the London stagecoach. He had intended to spend the next eight hours getting a good night’s sleep, not traipsing across the south Dorset countryside.

“What sort of accident?” It would be as well to make sure that he was not undertaking the journey merely to bandage some gentleman’s bruised finger.

“Lord Warbury will reward you handsomely for your services,” Moorecott said, as though he had not heard George’s question.

That was beside the point. This Lord Warbury might have plenty of money to throw about, but George was damned if he would go out of his way because his lordship had fallen over while drunk, or wanted an emetic after gorging himself on too many rich dinners.

The fellow, Moorecott, had spoken courteously, but in the voice of someone who was used to being obeyed. At first, George had taken him for a gentleman, but he must be an upper servant of some kind, in the service of this Lord Warbury, whoever he was. Moorecott’s coat and stock were black, and he wore his own dark hair, where George would have expected a powdered wig. But perhaps that was only for footmen these days. George didn’t know. He had very little to do with the servants of the aristocracy. In any case, whoever the man was, he was doubtless accustomed to using his master’s wealth and privilege to get whatever his master wanted.

“I’n’t there another surgeon hereabouts who’d like to enjoy his lordship’s largess?” George said dourly.

“There’s a surgeon over at Sutton Marshall,” the innkeeper put in. “But it’s nigh on an hour’s ride. Our own local fellow would have been closer, but he’s away at Lyme. Or there’s always the village barber, mind.”

“It’s rather urgent,” Moorecott said. “Have you a horse, Mr Evans?” When George shook his head, Moorecott turned to the innkeeper. “Perhaps you would be so kind as to see about a mount for Mr Evans?”

As soon as the innkeeper had left, the man turned back to George. He lowered his voice. “You’ll have to deal with two patients, both suffering gunshot wounds.”

“Christ. Why didn’t you say so before, man?” George snatched the case containing his surgeon’s instruments and bundled his other possessions into it. “Where are these wounds, precisely?” He shrugged into his coat and jammed his hat onto his head.

“One in the shoulder, one in the stomach.”

George stopped by the door, turning to raise an eyebrow at Moorecott. “What’s this, a midnight duel?”

Moorecott flashed him a sudden, unexpected smile. It was gone almost before George could be sure he had seen it. “You’re quick on the uptake, Mr Evans. And now you’ll understand the need for discretion, I trust.”

“I understand the need for getting there in a hurry.”

George had thought duels were customarily fought at dawn. But he would be the first to admit he was not overly familiar with the etiquette in vogue. If gentlemen wanted to go around shooting each other in the name of honour in the middle of the night, who was he to stop them?

Downstairs in the yard, the innkeeper had raised the stable boy, who was quickly saddling a sturdy grey mare for George. He took George’s small case and strapped it into the saddle bags.

“It’s about half an hour’s ride,” Moorecott said, swinging neatly up into the saddle of a glossy brown gelding.

George was obliged to accept the innkeeper’s help in order to scramble, rather less gracefully, onto the other horse. He could ride well enough—he had learnt as a young lad in the Dales—but it had been years since he had last had occasion to do so. The stirrups had been set for someone with average-length legs, not George’s long, lanky ones, and the stable boy hurried to adjust the straps.

Moorecott set a steady pace as they rode away from the inn. They soon left the road and cut across the downs, following a track Moorecott seemed to know. George had never been in this part of the country before and was obliged to rely on the other man, his mare following the lantern hanging from the bridle of Moorecott’s horse.

In the deep black sky above, a thin layer of clouds veiled the full moon. The crisp night air of late February burned George’s lungs, blowing away the last of his sleepiness and low spirits.

Around them, the heathland was eerily still, with only the soft thud of horses’ hooves on the mossy ground and, once, the screech of a barn owl. They had left the woodlands behind near the village, but scrubby bushes and the occasional isolated tree dotted their path, looming up out of the dark like lonely sentinels twisted into weird shapes by the prevailing wind.

After what felt like a long time, the lights of a building came into view. It was a solid two-storey structure of no particular architectural merit, and far too small to be the principal residence of an earl. Probably a hunting box, George thought, remembering that Moorecott had called it Dunstan Lodge. It wasn’t the hunting season, but the Earl doubtless found other leisure activities to occupy his idle hours.

A sleepy-eyed stable boy took their horses in charge, and Moorecott led George through a side door into the house.

They were met by a man in his late thirties, a little gone to seed, dressed well but plainly in the unassuming fashion of a professional man—a land agent or solicitor, perhaps. The candle in his hand revealed a pasty white face, and his manner was that of a man in shock.

“Mr Allam, this is the surgeon, Mr Evans,” Moorecott said to him.

“Thank goodness!” Mr Allam exclaimed. “I’ve put Lord Warbury in the salon. Come along, come along.”

“And where is Mr Thurlow, may I ask, sir?” Moorecott said as they followed Allam along a corridor lined with hunting trophies and blackened old family portraits.

“He’s also in the salon. It’s very awkward. Young Mr Henry Thurlow has been making a tremendous fuss about his father. His distress is quite understandable, but it’s been exceedingly difficult to deal with him.”

The salon turned out to be a large, oak-panelled room, furnished without ostentation in the style of the previous decade. Flames crackled in the imposing marble fireplace, and two sofas were drawn close enough to benefit from the heat. Both were currently occupied.

On the sofa to the left, propped against the armrest, lay a well-built man in his late thirties, dressed in what was probably the height of London fashion. The right arm of his coat had been cut off, and his shoulder was bound in a makeshift bandage, blood staining the white cloth. Allam went to him immediately. “The surgeon is here, Warbury.”

The man on the other sofa was considerably older, perhaps in his late fifties. He lay flat on his back, his legs propped up on the armrest, his eyes closed. Seated beside him was a pale-faced boy, holding some sort of compress to the older man’s stomach. At the sight of George and Moorecott, the boy sprang to his feet.

“At last! Not a moment too soon. My father could bleed to death here for all you monsters care—”

“The compress, Mr Henry,” Moorecott said, his voice surprisingly gentle. The boy swallowed and sat down abruptly, returning to his task.

George cast a glance at the fashionable fellow with the shoulder injury, decided his case appeared less urgent, and turned to the older man lying flat on his back.

“Over here, if you please,” Allam called from the other side of the room. “Lord Warbury needs you.”

“I’ll decide who needs treating first,” George said flatly, without turning round.

To his relief, he was not obliged to deal with Mr Allam, as Moorecott intervened.

George put down his case and knelt by the sofa. “It seems you’re Mr Henry Thurlow?” he said to the boy, who nodded, lips pressed tightly together. “I’ll need you to stand aside for a moment and let me take a look at your father, all right?”

The elder Mr Thurlow had been shot in the lower right abdomen. A sheen of sweat covered his forehead, and he was drifting in and out of consciousness. When George laid a hand on the compress, he came to, letting out a yelp of pain.

Someone had done a decent job of bandaging the wound. George took a pair of scissors from his case and made a few judicious cuts in the linen cloth, pulling it aside.

The bullet did not seem to have hit any major arteries, though it must have come dangerously close to the coeliac trunk. There was no exit wound.

George feared the bullet was still in the body, and worse, a good part of the man’s shirt as well. The bullet was not necessarily a problem. George had sewn up plenty of men with buckshot still inside and seen them go on to live for many more years. But this bullet was badly placed, and the scraps of shirt linen would considerably increase the risk of infection. He would have to operate, but for that, he would need more light and better conditions than this cramped sofa.

He looked up to find Moorecott at his elbow.

“How long has it been since he was shot?”

“Perhaps an hour and a half,” Moorecott answered.

“Who dressed the wound?”

“I did. How is he?”

“Not in immediate danger of death. He’s been reet lucky.” He scrutinised young Mr Henry Thurlow out of the corner of his eye and decided not to go into further detail. The young man was a deadly white and looked ready to swoon at any moment.

George finished applying a new dressing, then gave Mr Henry strict instructions on keeping pressure applied.

“Aren’t you going to… to sew him up?” the young man asked in a quavering voice. At first, George had thought him a mere boy, but up close he appeared to be around eighteen or nineteen. The resemblance to his father was striking. They had the same heavy brows and watery blue eyes.

“Yes. Soon.” George got to his feet. “I’ll take a look at the other fellow now.”

“The ‘other fellow’ is the Earl of Warbury,” Moorecott murmured, leading him across the room.

This was presumably intended to inform George of the proper mode of address. George ignored it.

Warbury was reclining on the sofa. Allam was still kneeling by his side, clasping one of his hands and speaking to him in a low voice. Warbury’s eyes were closed, but he opened them upon George’s approach.

“How’s Thurlow?” he murmured. “Still alive?”

“He’s in a stable condition, my lord,” Moorecott said.

No thanks to you, my lord, George thought, but didn’t say aloud. He neither knew nor cared to know what had driven Warbury and Thurlow to a duel.

Allam moved aside to allow George to kneel by the sofa. A tight tourniquet had been tied around Warbury’s upper arm, and the wound had been competently bound, presumably by Moorecott. George undid the bandages.

The bullet had grazed the upper arm, leaving a red, angry weal. It had bled profusely, but the tourniquet had done its job. The wound appeared clean, with no cloth or dirt sticking to it, though there was always a danger of traces of gunpowder poisoning the system.

“Well?” Warbury demanded. “What’s the verdict?”

“Nowt to worry about. I’ll apply a balm and a new dressing.”

“He won’t lose the use of his arm?” Allam asked.

“I hardly think so,” George said shortly. He was not unsympathetic to Allam’s obvious concern for Warbury’s well-being, but he had no time to pander to it just now. He looked up at Moorecott. “Is there any laudanum in the house? I have a little with me, but not as much as I’d like, and I maun save it for Mr Thurlow.”

“I fear not,” Moorecott said.

“Never mind that,” Warbury said. “Clean me up, sawbones.” He managed a faint smile. “It’s not mere bravado, I assure you. I’ve been sewn up without laudanum many times before. I saw a little action in the Navy, you see.”

“As you wish.” George got to his feet, turning to speak to Moorecott. “I’ll need water—hot, if possible—and linen for bandages. Also egg yolk, and a bottle of turpentine if you can find some.”

Moorecott and Allam helped Warbury lie back down, while George glanced across at Thurlow, unsure how best to proceed. He needed to see about setting up a place to operate on that stomach wound, but he hesitated to broach the subject with Warbury or Allam. He didn’t know what circumstances had led to the duel, but he did not think it appropriate to discuss Thurlow’s health with the man who had shot him, even if that man were an earl and the owner of this house.

“A word, Mr Moorecott?” he said quietly.

Moorecott nodded. “Come to the kitchen.”

Allam had knelt by Warbury’s head, taking his hand again. “Another glass of brandy, perhaps, Moorecott,” he called.

“Very good, sir.” Moorecott bowed and withdrew, indicating to George to follow him. “Your conclusions, Mr Evans?” he asked as he led the way down a narrow corridor into the servants’ quarters.

“Warbury will soon recover, I make no doubt. The problem is Thurlow. He needs to go under the knife. The bullet’s still in the wound, along with a good part of his shirt.”

“Ah.” Moorecott winced. “I feared as much.” He opened the door to the kitchen, waving George courteously ahead of him. “It cannot wait long, I presume?”

“It would be better not to wait, no.”

“Can you do it?”

“Yes, of course.”

George had spent the past five years working in the borough of Southwark, where he dealt mostly with accidents in the workshops and factories or on the wharves: limbs crushed in machinery or broken in a fall. But during his apprenticeship in Yorkshire, he had seen a different range of injuries, including plenty of hunting accidents involving buckshot or musket balls. This was the first time he had ever been called upon to deal with a wound from a duelling pistol, but the same principles applied.

“Very well,” Moorecott said. “Give me a few minutes to get his lordship to bed and to set up some more suitable place. I suppose a solid wooden table, better lighting…?” As he spoke, he had been searching in a cupboard. He turned, holding a bottle of turpentine, and set it on the table.

“Aye, that’d be best. Also hot and cold water, and plenty of bandages. Linen sheets, or some such thing.”

Moorecott nodded. “The eggs are in the pantry. Help yourself.” He picked up the candle again and disappeared up a flight of stairs in the corner, returning a few minutes later carrying a stack of folded sheets.

George fell to ripping sheets, while Moorecott stirred the embers of the fire to life and set a pot of water over it. George watched him move quietly around the kitchen. He was smartly dressed in good quality garments and, meeting him on the street, George might have taken him for a gentleman—though the clothes were probably Warbury’s cast-offs. He spoke like a gentleman, but his voice held a touch of the North, not dissimilar to George’s own.

Now he was deftly breaking eggs into a bowl for Warbury’s balm, a little frown between dark brows as he concentrated on separating the yolks from the whites. George noticed that he was missing two fingers on his left hand. Everything he did had an air of quiet competence. He would probably make a useful assistant in the surgery.

Watching him at work, a thought struck George. “Are you the only servant in the house? Waiting on all that lot?”

“A woman called Mrs Boyce lives in a cottage on the grounds and comes in during the day. And there’s the stable boy, of course.”

George chewed that over in his mind. “I always thought earls only moved about the place with a groom, a valet, and at least twenty footmen.” He was exaggerating for effect, and was gratified when Moorecott let out a short laugh.

“Lord Warbury likes quiet and informality when he comes down here.” He lifted the boiling pot of water off the fire. “He has plenty of footmen at his ancestral seat in Wiltshire, I assure you.”

“Still, seems a bit hard on you.”

Moorecott glanced up, the hint of a smile on his lips. “Perhaps it will reassure you to learn that Mr Thurlow and his son are not a settled feature of the household. They arrived this afternoon, unexpectedly. I normally only have his lordship and Mr Allam to wait on.”

“Oh?” Despite his resolution to take no interest in the affairs of gentlemen, George was growing curious about the presence of the Thurlows in this house.

“These are Mrs Boyce’s sheets we’re tearing up, by the way,” Moorecott added. “I hope she won’t take it too hard when she discovers what I’ve done.”

“You can always blame it on me.”

Moorecott grinned. “Don’t worry, I will.”

Most of the time, he had a reserved, serious demeanour, but George had seen his quick smile several times now. A series of white scars ran under his ear, from wounds that should have received stitches but hadn’t, and they stretched when he smiled. He had a nice smile. George wouldn’t mind seeing it again.

He cleared his throat. “And can you get that young lad out of the way? I don’t want him there while I’m operating on his father. He’s a bundle of nerves.”

“Agreed.”

George made up a balm of egg yolk and turpentine for Warbury’s wound, mixed with a dash of oil of roses from his own travelling case. He let the familiarity of the work soothe his nerves in the face of the daunting task that lay ahead of him. He had plenty of experience and was confident in his skills, but even the best surgeons in the best of conditions lost as many as half their patients. And these were not the best of conditions.

But there was no point letting nerves get to him. If Thurlow’s wound was left to fester, that would be the end of him. And George could not let that happen.